methods+methodologies

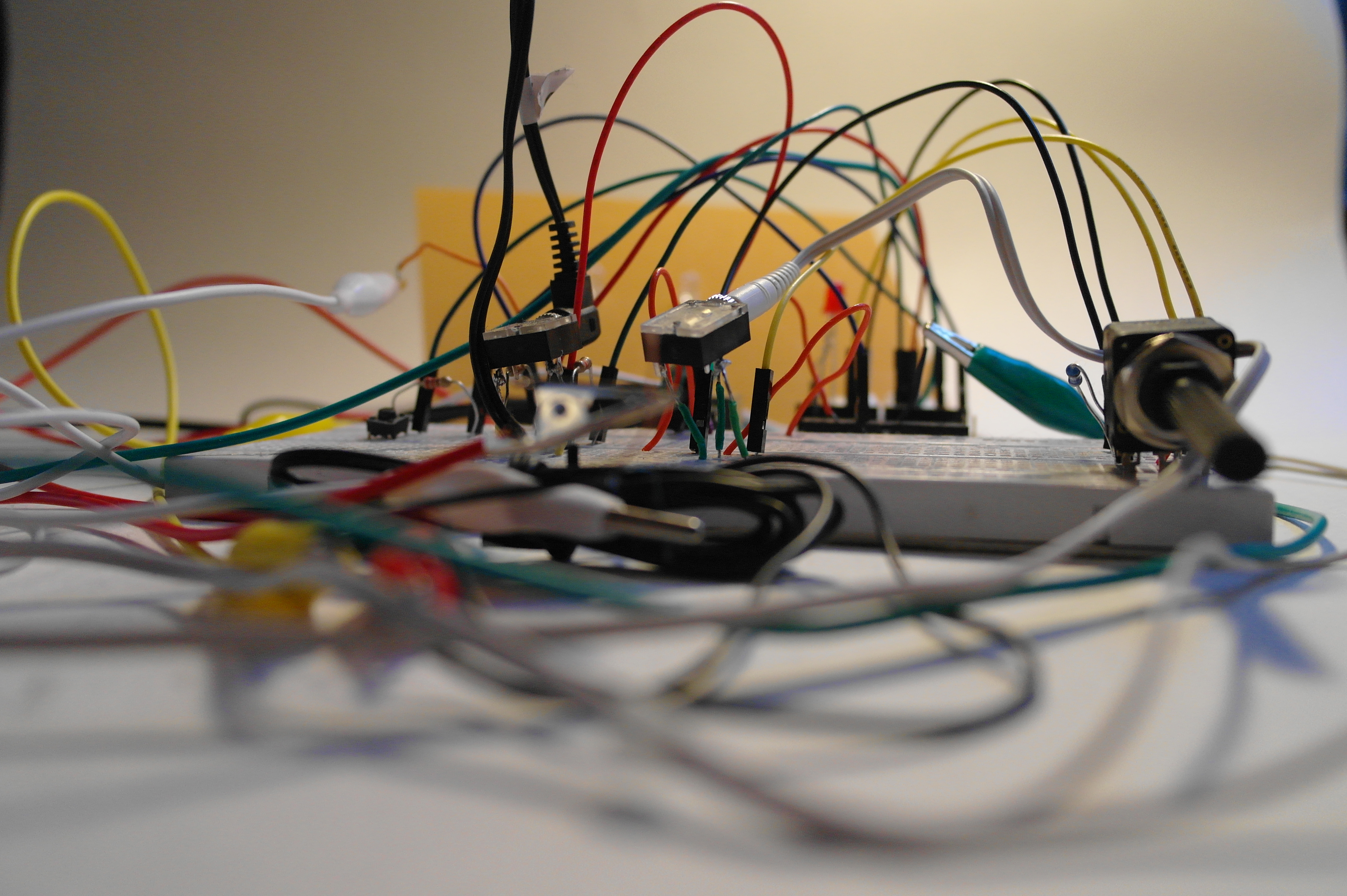

Our project relies on feminist hacking as an art-based research method. Feminist hacking involves a intensive knowledge-sharing process, through workshops and other forms of exchange. Feminis hacking is structured around breaking with feminine gender scripts, transgressing gender norms and embracing technological challenges.

This usually involves disassembling electronic devices on purpose, with the intention of learning and understanding, but also reassembling, them into something els and creating art. It implements recycled hardware and it is informed by critical making. Feminist hacking is about developing artistic technology, based on open hardware, from a queer and female perspective.

We define our approach as qualitative and from

the genre of research-in-action within an iterative and spiral course. Our method is empirically based, all steps and findings are hacked, discussed, reflected, reconsidered, re-hacked and re-discussed.

We aim to harness open hardware for non-binary, queer and feminist artists, and to enable

unorthodox alliances.

We believe the development of individual positions through collaboratively developed hardware to be the most appropriate way to demonstrate what feminist hardware entails. This methodology aims to support, on the one hand, the production of new knowledge acquainted by the interaction between artists, hardware developers/manufacturers, and, on the other, the production presentation and dissemination of artworks and reflections resulting from this exchange.

Feminist hacking embraces a “Diffractve methodology for artist practice” inpired by the work of Rosi Bradotti, Karen Barad and Donna Haraway.

Feminist hacking embraces a “Diffractve methodology for artist practice” inpired by the work of Rosi Bradotti, Karen Barad and Donna Haraway.

On Diffractive art practices:

Rosi Braidotti has emphasised the opportunity in today's fatigue in theory. By thinking of ourselves as "in this together" we can truly engage in practices not harmful to, but in line with the very figurations we live with and work on reciprocal understanding. Karen Barad also includes molecules and nanoparticles into her account, when she explains that matter and meaning cannot be dissociated (Barad, 2007). From an "entangled state of agencies'' (Barad 2007, p.23) we seek to understand how our own situatedness comes to matter. Bennett's notions of vital materialism, Braidotti's views on feminist new materiality, and Barad's diffractive approach all frame differences as crucial, rich in conclusions asking to be drawn and always changing, lacking an essence and lacking a final stage. Differences are like waves diffracting with other waves, sometimes cancelling each other out, but in a different phase exponentially emphasising each other's amplitude. Conflicting tendencies, interests and growth therefore are equally never graspable, never easy to be judged, yet we can swing with their ever entangled and communicating iterations, like troubling rhythms. Haraway reminds us one more time that staying with this trouble is the method to get the closest empirical gaze on what is real. Similarly, hacker practices from Ghana, Mexico and Indonesia resonate with hacker practices from Germany, Greece, Canada and other regions of the world. Growing along the lines of power among nation-states, like mould, follows existing traces of food and sugar. For feminist hacking this entails being/staying on the move, not giving into fast solutions, but instead iteratively performing vitalist connectivity.

In “Overlapping Waves and New Knowledge Difference, Diffraction, and the Dialog between Art and Science”, art historian Susanne Witzgall (2016) criticizes the divisive and generalizing attitudes, in which artistic research is frequently defined as something that generates implicit, practical, or sensual knowledge, which is difficult to verbalize and is rather shown or felt. And while credited with cognitive and rational qualities, it is in certain sense deprived of legitimization as theoretical-discursive knowledge. Such descriptions operate together with the reflexive understanding of scientific study with which artistic research conflicts and from which it feels obligated to differentiate itself, based on sensory and conceptual distinctions. This approach is sometimes accompanied by the concern that scientific procedures would eventually get the superiority, robbing artistic research of its distinct aesthetic qualities.

Witzgall argues that to determine if and how interdisciplinary collaboration between art and science produces new results, it is important to examine the character of the interaction, where the goal must be to establish and prove the relationship, as well as to assert the distinction between art and science. At the same time, hierarchization and stereotyping should be avoided, as they frequently reduce art to the position of explanatory illustration, silent visual transmission, or a welcome element of havoc in multidisciplinary environments, whereas science, on the other hand, is seen as the custodian of research.

To avoid such attitudes, Witzgall suggests to think with three philosophers, Gilles Deleuze, Gilbert Simondon and Karen Barad. Namely, she proposes Gilles Deleuze's idea of free difference (Deleuze, 1994) and his elaboration of Gilbert Simondon’s concept of ‘Individuation,’ as a more constructive method of addressing the symmetrical and nonhierarchical interaction between art and science. Witzgall draws a parallel between the indeterminacy of differential relations from philosophy and quantum physics as explained by Deleuze and Barad to assert the divide between art and science as a positive difference.

to turn difference into a positive, to free it from its static and eternally hierarchical containment within the conceptually conformist intuition, within the sensible, and to instead comprehend difference as an active, eventful principle — Deleuze desires to deliberately “think difference in itself independently of the forms of representation” (Deleuze, 1994., p. 19). In order to achieve this, he leaves the surface effects of rep- resentation behind, descending into the depth of Being, which he himself regards as (given) difference. This Difference of Being is a(n) (individuating) difference of intensive quantity, which precedes those which we know as generic and specific differences, or individual differences (compare ibid., pp. 38).

(Witzgall, 2016, p. 144)

Witzgall discusses the question of Idea in Deleuze, who considers those

“genuine objectivities”, made up of “differential elements and relations” and equipped with a specific mode — “the problematic” (ibid., p. 144).

She notes, that to Deleuze, the Idea distinguishes itself through a multiplicity, whose elements initially do not have a

“sensible form nor conceptual signification, nor, therefore, any assignable function. They are not even actually existent, but inseparable from a potential or a virtuality” (ibid., p. 183). It is precisely this character of the Idea that renders possible the manifestation of difference as something freed from all subordination. Only in a subsequent step must these elements of the Idea’s manifold indetermination be defined in reciprocal relations.

(Witzgall, 2016, p. 144)

Witzgall also complements Barad’s idea of intra-action with Gilbert Simondon’s transductive process of individuation which according to the author, is missing from Barad's concept of intra-action and which denotes the path taken by invention in the field of knowledge.

Simondon views the transductive process as a complicated process of organization, change, and transfer that preserves and integrates opposing features. He distinguishes between transduction domains that are simple and those that are more complicated. In the case of more complicated domains, the former happens as progressive iteration.

In the area of knowledge, the transductive process indicates the actual course taken by invention. Its progress is neither inductive nor deductive, but rather transductive, “correspond[ing] to a discovery of the dimensions according to which a problematic can be defined” (Witzgall, 2016, p. 149).

The transduction process implies that scientific and creative knowledge production systems are modified as a result of transdisciplinary synergies as they continue to individuate.

In connection with the dynamics of intra-action — or, to borrow Simondon’s terms, in connection with mediation as a principle of individuation and its relational dimension—the transduction process suggests that the systems of scientific and artistic knowledge production are themselves transformed in the process of their continued individuation through interdisciplinary encounters and collaborations. As complex metastable systems, they could, in the long- term, through their mutual communication with elements of another discipline, expand into unfamiliar epistemic areas, wherein new knowledge is generated. (Ibid, p. 150)

Barad's notions of diffraction and diffractive methodology, according to Witzgall, provide grounds for a short- and medium-term interdisciplinary dialog between art and science to gather information.

[...the mutual reading-through-one-another—by both artists and scientists — of various disciplinary forms of entanglement with the world would not only illuminate the particular peculiarities of respective boundary-drawing practices and generated differences, but in a united epistemic practice it would, at the same time, produce new difference or diffraction patterns, thereby generating new forms of knowledge. (Ibid, p. 150)

She concludes by emphasizing two closely linked aspects of the collaboration between art and science:

- The overlapping of two different knowledge-generating engagements and interferences of subject, apparatus and examined phenomena can produce new diffraction and difference patterns of intra-active epistemic boundary-drawings and shape-givings.

- This occurs, however, only when the distinct diffraction patterns of both disciplines are equally strong, that is, when they do not exist in a hierarchical relationship, because otherwise neither perceptible constructive nor destructive interferences may emerge. This can only happen if we regard the contrast between art and science as a positive difference.

(Ibid, p. 151)

Jane Prophet & Helen Pritchard are among the first to explore the diffractive art practices in two instances. One is the framework of artificial life art (2015a), where they question the application of the term ‘agency’ and give preference to the more relational new materialist term ‘agential’ which destabilizes the subject-object binary. In another instant (2015b) they consider the generative entanglements between media art and contemporary art practices as ‘the “always-already” entangled practices of art , namely ‘the entanglement of material practices and the entanglements of the ways we articulate the practices of art and the practices themselves.’ In short, they are ‘emerging from the patterns of interference that are sometimes revealed through artworks.’ (ibid)

Belsunces et al (2017) propose ‘diffractive interfaces’ as a research approach centered on the relation between art and pedagogy, as a method of allowing dynamic interaction through experiments with different relational patterns. They develop alternative (re)presentation and gesture movement within cultural interfaces, which becomes a ‘catalytic space for intra-action, a generative metaphor, aesthetic event, socio-material framework and political device.’ Such a framework is a series of research tools that can destabilize the ontological violence of certain systems of representation and pre-established agents. It can also encourage the development of other ways of understanding the world and generating knowledge beyond the supremacy of reflective processes as a vehicle for the articulation of sensible orders.

As a result, the intra-actions of the collective entity created in a learning setting manifest as mutation into a metastable equilibrium (a false equilibrium that will be broken when any of the elements that compose it change). It leads to a condition of hilomorphistic pre-individuation in which the focus is on the process of becoming, rather than the ultimate form.

Amba Sayal-Bennett (2018) investigates the disruptive ‘material effects of difference’ in film and video, namely the distortion resulting from the clash of two different mediums – in the artworks of Cory Arcangel and Steve McQueen.

Here, diffraction is an operative mode which functions at two levels. The first relates to the layering of media, and the second is affective: quoting Lenz Taguchi, the researcher is entangled,, in the ‘transcorporeal process of becoming-minoritarian with the data..’ Engaged with the data, the researcher is aware of the bodymind faculties that record scent, touch, pressure, tension, and elicit association that emerge between matter, and discourse.

This concept of becoming-minoritarian emphasizes a key distinction between diffractive and representational analyses — transformative and non-transformative inquiry approaches. Diffractive analysis generates the researcher's and the investigated artist's and artwork's mutual enfolding, or intra-action. (Sayal-Bennet, 2018)

Scurto et al (2021) suggest a diffractive methodology for design research, specifically in the field of machine learning within material-centered interaction design. The authors propose such method as a way of ‘revealing the computational materiality of ML’ and uncovering the role of embodiment in ML prototype crafting, which can redefine the approaches to ML. They outline five interference conditions for art-based ML prototypes, namely a ‘situational whole, small data, shallow model, learnable algorithm, and somaesthetic behaviour’— and describe how those can expand the design and engineering practices of ML. The authors propose a process of intra-active machine learning which positions materiality as a ‘entry point for ML design within HCI.’ Small data, shallow models, and learnable algorithms may be used to create ML prototypes that yield unique somaesthetic behaviors that can be experienced and debated by a variety of practitioners. Through diffractive practice, the socio-technical conditions obtained for crafting art-based ML prototypes open the way for an intra-active understanding of ML that accepts disparities between design and engineering approaches.

Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition. Columbia University Press.

Prophet, J., & Pritchard, H. (2015). Performative apparatus and diffractive practices: An account of artificial life art. Artificial Life, 21(3), 332-343.

Belsunces, A., Valero, L. B., Brandstätter, U., Escudero, C., Lamoncha, F., Pin, P., & Tomás, E. (2017). Diffractive Interfaces: la difracció com a metodologia d'investigació artística. Artnodes, (20).

Prophet, J., & Pritchard, H. (2015). Diffractive art practices: Computation and the messy entanglements between mainstream contemporary art, and new media art. artnodes, 15.

Sayal-Bennett, A. (2018). Diffractive analysis: Embodied encounters in contemporary artistic video practice. Tate Papers, 29.

Scurto, H., Caramiaux, B., & Bevilacqua, F. (2021, June). Prototyping Machine Learning Through Diffractive Art Practice. In Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2021 (pp. 2013-2025).

Witzgall, S. (2016). Overlapping Waves and New Knowledge Difference, Diffraction, and the Dialog between Art and Science. In Recomposing Art and Science (pp. 141-152). De Gruyter.